START VOL. 4 NO. 11 / JUNE 1990 / PAGE 30

From the eerie surrealism of Menace to the demonic imagery of Baal, Psygnosis' graphics stand out in the game world for their consistent high quality. START correspondent Richard Monteiro traveled to Psygnosis' Liverpool office to talk to the artists behind the scenes.

Whatever your gaming preference - adventure, arcade action, shoot'em up or strategy - you can doubtless point to any Psygnosis title as an example of "how it's done." But it's probably not the range of game genres for which you best remember Psygnosis, nor even the addictive quality of the games. Most likely, it's the graphics that stick in your mind.

At Psygnosis, graphics are all important. As John White, product development manager, puts it, "Unlike sound, you cant switch off a game's graphics; they are present from beginning to end of a game. First impressions count. Half the battle is won if the visuals are interesting."

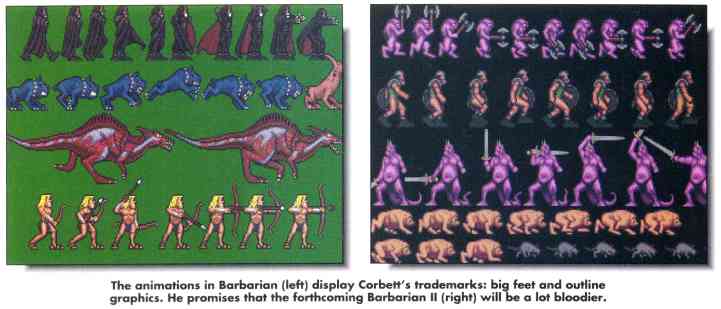

Interesting visuals in games such as Arena, Cronous Quest and Barbarian first brought Psygnosis attention. Their Barbarian was arguably the first game to show the difference between 8- and 16-bit machines. While the sound and gameplay caused excitement, it was the graphics that really stood out, and still stand out today. The detailed backdrops, the animation, the comical sprites - it was the beginning of something special.

The Sprite

Brigade

Today that something special comes from their

stable ot artists: Garvan Corbett, Jeff Bramfitt, Jim Bowers and Neil Thompson.

(Editor's note: Thompson declined an interview since he joined Psygnosis very

recently.) So strong is Psygnosis' commitment to graphics that it employs these

four men full-time in-house, while using freelancers for coding and game

development. The art team cleans up sprites and animations created by outside

programmers, draws title screens and loading sequences, and designs the graphics

for many games from scratch.

The artists use Commodore Amigas running Deluxe Paint III to do all the design work. Psygnosis chose the Amiga because it can emulate the ST's low resolution (320 x 200) 16-color mode, while the ST is incapable of emulating the Amiga's 32-color low-resolution mode. Once the artists have tweaked 16-color graphics designated for the ST, they give programmers Amiga disks containing images in IFF format for conversion and subsequent manipulation.

What, Me Hurry?

Compared to most software houses, Psygnosis' working practices are odd.

There is no rush to get the job done. A game is finished when everyone agrees

they've done their best.

"There is no time limit when designing the graphics for a game," Corbett says. "I like to get the job done in six months, but it doesn't matter if it takes longer. It's getting the game to look good that's important."

The four artists have free reign over a game's graphics. They're given a rough story outline by the programmer or game designer, then the artists are on their own. They decide upon the look of every sprite, every animation, every background, the startup screen - everything.

|

|

But that liberty is a two-edged sword.

"It's great having that sort of freedom," Corbett says. "What's not so great is coming up with the ideas."

Bowers agrees. "It's very easy to spend three weeks out of a month scratching your head looking for inspiration and the final week sitting down to draw."

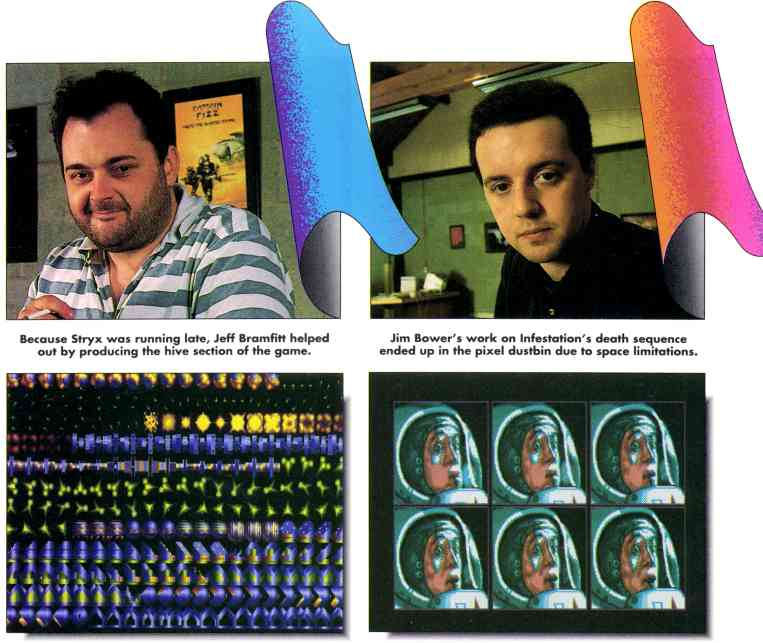

Meticulous detail often clashes with space constraints; a lot of graphics end

up shelved. "Designing computer graphics is much like writing," Bramfitt

explains. "You can't get too attached to your work. Just as editors will chop

text, so programmers and game designers will remove sequences of animations and

sprites."

|

|

Alter seeing his work end up in the pixel dustbin, Corbett doesn't produce as much now. Bowers, on the other hand, takes a philosophical approach. "Yeah, well, it's the way of the world," he says.

Who's Who

Each of the Psygnosis artists generally works on a different project,

although each has his own specialty that might he called upon from time to time.

Garvan Corbett joined Psygnosis five years ago on the recommendation of a friend who worked there. At the time he was enrolled in a government-sponsored workfare program, since the job market for artists was tight. All three illustrators, in fact, spent time on that workfare program; Bramfitt was Corbett's and Bowers' boss.

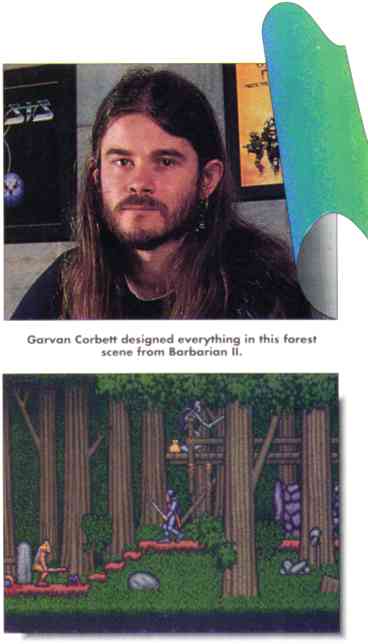

Corbett never used a computer for design work until he joined the software company. "The ST was the first machine I came in contact with and DEGAS Elite the first drawing package." So far he's been responsible for the graphics in Bratacus, Deep Space, Barbarian and Stryx.

Corbett's forte is designing cartoon characters. "I just love Disney cartoons, and especially Tom and Jerry," says the largely self-taught 28 year old. "I learnt so much simply by studying the animations."

It's easy to spot Corbett's work since, he claims, "big feet and outline graphics are my hallmark." According to one of the Psygnosis game testers, Corbett also enjoys producing pencil drawings of large, intimidating women with forked tongues. Unfortunately, Corbett wasn't willing to show off these.

Barbarian II is Corbett's latest project. He'll produce the animations for the characters and design the backgrounds. Since he illustrated the original Barbarian, however, he has a head start.

"Just as programmers build up libraries of source code," he explains, "so we accumulate disks full of characters and other graphics. It's possible to get away with the same ideas - and often the same characters - over and over again. Barbarian II is a great example. I was responsible for the first version and consequently have all the frames from the early game. Naturally there will be vast improvements to the sequel and the character you control will probably have 100 frames of animation."

After his stint on workfare, Jim Bowers applied his art foundation coursework to sketching kitchen layouts for an interior design firm. Two and a half years ago, about the time he got bored with refrigerators and sinks, his friends from workfare offered him a job at Psygnosis. He, too, had never used a computer for design before, hut quickly grasped the overall scheme of things.

Bowers is a loading-sequence and 3D-design man. His work includes the loading sequences for Obliterator, Matrix Marauders (not released yet) and Infestation. He also crafted the 3D graphics in Infestation.

You'd be forgiven for thinking Bowers produced most of his work with help from a video digitizer. It's his technique. "I go for impression rather than detail," he says. "Shades and subtlety are what give my graphics their digitized look." The results speak for themselves. Unless you saw Bowers in action at the keyboard, you'd be convinced he hid a video digitizer and camera in his pocket.

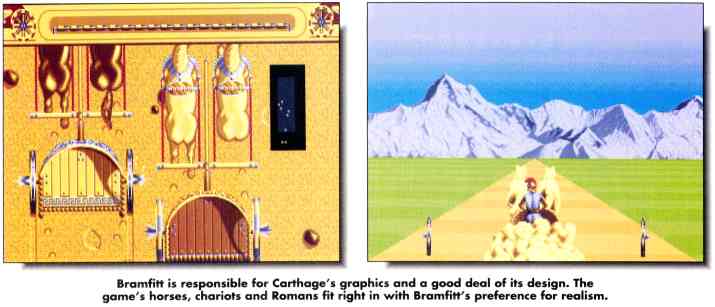

Friendly rivalry exists between the artists. Jeff Bramfitt loathes video digitized graphics and cartoon characters with big feet. He prefers realism to surrealism. For the past year Bramfitt has been designing Carthage, a strategy game set in the Roman era complete with Ben Hur-style chariot racing.

Like Corbett, Bramfitt has a conventional design training behind him. Computers and art did not mix at the polytechnic I attended in Liverpool," Bramfitt remembers. "Indeed, computer art was and still is frowned on by illustrators and fine artists.

"Joining Psygnosis was a bit of a shock. I came to the interview, they sat me down in front of a computer and told me to draw a picture. I was there all day drawing this image pixel by pixel."

Bramfitt started life at Psygnosis three years ago designing title screens

and death sequences. His work appears in Barbarian, Terrapocis and Aqua

Adventurer.

|

drawing before joining Psygnosis. |

Not By Design

None of the artists at Psygnosis used a computer for drawing before they

joined the software firm. But then, they weren't hired for their technical

know-how; they landed their jobs because they knew how to draw.

Their most difficult task is achieving realistic motion. Bowers tends to look at his reflection in the screen or gets someone to walk across the floor when animating a certain part of the body. Observation is extremely important, they say. Bramfitt studies the work of Eadweard Muybridge, a 19th-century photographer who produced countless books full of animals in motion.

Not all aspects of traditional art training are useful, however. Forget about using paper, unless it's graph paper. Sketching on paper can be deceptive, they warn; you never achieve the same smooth curves and lines on a computer simply because pixels are so blocky. "I only ever use paper when messing around - for throwing paper darts at Jeff and Jim," Corbett says. What a great idea for a game! Art Wars: three men launching and dodging a storm of deadly paper darts. The gameplay will be simple, and since Psygnosis will publish it, the graphics will he spectacular.

Richard Monteiro is a freelance computer Journalist in England. He has previously edited ST Format magazine and now writes for numerous entertainment and home-computer magazines.